In the early 1980s, the A&W restaurant chain released a new hamburger with the intention of rivaling the McDonald’s Quarter Pounder. The new A&W burger had a third-pound of beef, cost less than the Quarter Pounder, and in taste tests, customers preferred the A&W burger. The A&W launched a national campaign touting these benefits, but instead of rushing to A&W, customers snubbed it.

In the early 1980s, the A&W restaurant chain released a new hamburger with the intention of rivaling the McDonald’s Quarter Pounder. The new A&W burger had a third-pound of beef, cost less than the Quarter Pounder, and in taste tests, customers preferred the A&W burger. The A&W launched a national campaign touting these benefits, but instead of rushing to A&W, customers snubbed it.

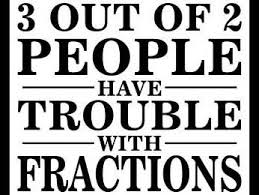

Through focus groups, A&W discovered the answer to the bewilderingly poor market performance of its burger: Americans do not understand fractions. Failing to understand that one-third is greater than one-fourth, customers believed that the A&W burger had less meat than the Quarter Pounder and therefore felt that they were being ripped off. Why, they asked the researchers, should they pay the same amount for a third of a pound of meat as they did for a quarter-pound of meat at McDonald’s. The “4” in “¼,” larger than the “3” in “⅓,” led them astray.

This is a striking example of our national innumeracy – the mathematical equivalent of illiteracy. Americans are not good at math. The New York Times recently published an article on this very subject and we at MathSP were so taken with its discoveries that we are to widen its audience.

The False Starts of Overhauling Math Education

Why are Americans lagging in math achievement? The answer has everything to do with our inability to translate our groundbreaking ideas about how to optimally teach math into actual classroom instruction. To clearly illustrate the disconnect between our ideals and our practices regarding math education, The New York Times introduces us to Akihiko Takahashi.

Akihiko Takahashi is one of the most revered math educators in Japan. His mentor, Takeshi Matsuyama, was an elementary school teacher who, unlike many of Takahashi’s elementary school teachers, boldly implemented cutting edge classroom exercises that got students thinking critically and inventively about the principles, patterns and relationships that constitute mathematics. Instead of memorizing formulas for the area and perimeter of a square, for example, students of Matsuyama would derive the formula for the area of a rectangle by engaging in passionate discussions that leveraged what they already knew about geometrical properties. Like the very first mathematicians, Matsuyama’s students had to harness the mathematical principles they’d already discovered in order to discover new properties and relationships.

This revolutionary approached enthralled Takahashi. When Takahashi met Matsuyama, he was young and in search of his calling. Matsuyama’s inspiriting take on optimal math instruction won Takahashi over and he subsequently joined Matsuyama in his fervor to discover the keys to forging the kind of math education that would yield brilliant and creative problem solvers.

Where did Takahashi get his bold ideas on math education? From reformers at the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics (NCTM), an American group that published manifestos throughout the 1980s that promoted cutting edge changes in the teaching of math. In turns out that in the realm of math education, Americans have never suffered from a scarcity of inventive and effective ideas. It’s simply in the execution of those ideas that we stumble.

Our Failure to Translate Ideas into Practice

According to the New York Times article, America has been attempting to revolutionize the teaching of math since the 1800’s. For centuries, reformers have been innovating groundbreaking techniques to cultivate critical thinking and problem solving and for centuries, these big movements falter from mass confusion and mass unwillingness to stray from the norms.

We are currently in the throes of one of these big pushes as across the country, states implement the Common Core. The Common Core is a set of academic standards that was designed to supplant states’ individual curriculums and hold students across the nation to a common standard. Educators and politicians from 48 states coalesced to write the standard in 2009. The Obama administration adopted the standard and made its implementation a prerequisite for receiving a portion of the $4 billion in Race to the Top grants. Today, 43 states have adopted the standard.

Responding to a recent survey by Education Week, teachers said they had typically spent fewer than four days in Common Core training, and that included training for the language-arts standards as well as the math standards.

We’ve provided teachers with a slightly different curriculum but we haven’t empowered them to teach that curriculum differently, meaning that we are once again repeating this cycle of generating wonderfully idealistic changes to the curriculum without providing the infrastructure to actually realize these changes.

What’s the Problem?

The cyclical pushes that have arisen since the 1800s to change the way we teach math comes from the longstanding idea that the traditional way of teaching math simply does not work.

The evidence is bountiful. On national tests, nearly two-thirds of fourth graders and eighth graders are not proficient in math. More than half of fourth graders taking the 2013 National Assessment of Educational Progress could not accurately read the temperature on a neatly drawn thermometers. (They did not understand that each hash mark represented two degrees rather than one, leading many students to mistake 46 degrees for 43 degrees. On the same multiple-choice test, three-quarters of fourth graders could not translate a simple word problem about a girl who sold 15 cups of lemonade on Saturday and twice as many on Sunday into the expression “15 + (2×15).” Even in Massachusetts, one of the country’s highest-performing states, math students are more than two years behind their counterparts in Shanghai.

Math innumeracy afflicts Americans well into adulthood. A 2012 study comparing 16-to-65-year-olds in 20 countries found that Americans rank in the bottom five in numeracy. On a scale of 1 to 5, 29% of them scored at Level 1 or below, meaning they could do basic arithmetic but not computations requiring two or more steps. One study that examined medical prescriptions gone awry found that 17% of errors were caused by math mistakes on the part of doctors or pharmacists. A survey found that three-quarters of doctors inaccurately estimated the rates of death and major complications associated with common medical procedures, even in their own specialty areas.

The Need for Better Teacher Preparation

Research shows that Japanese students initiated the method for solving a problem in 40% of the lessons; Americans initiated this method 9% of the time. Similarly, 96% of American students’ work fell into the category of “practice,” while Japanese students spent only 41% of their time practicing. Almost half of Japanese students’ time was spent doing work that the researchers termed “invent/think.” American students spent less than 1% of their time on it.

Why is it that Japan is so far ahead? Teachers. In Japan, teachers benefit from jugyokenkyu, which translates literally as “lesson study.” Teachers are provided with ample time to experiment with new teaching techniques and to exchange tips. They sit in on each other’s lessons and provide fruitful critiques. Too, in Japan, the teaching profession is held in much higher esteem than it is here at home.

To cure our innumeracy and empower problem solving skills, we must confront the fact that the traditional way of teaching math does not work. It is mind-numbingly rote and only succeeds at teaching students how to find answers, not how to think critically. The task of math education is to get students to see math not as a list of rules but as a way of seeing the world.

Too, we must provide more effective and thorough training for our teachers.

MathSP, Georgia’s Secret Weapon

At MathSP, we know how to teach math so that students develop a rock-hard understanding of the patterns and relationships that constellate the world of STEM.

Whether you’re seeking academic coaching in the humanities or in math and sciences, we’ll do more than just address your gaps and enable you to achieve solid grades – we’ll impart STEM fluency so that you’ll be able to confidently and competently tackle the educational challenges that lie ahead in college and in life.

STEM fluency is the ability to problem solve, think critically and logically, apply theory and innovate. STEM fluency is a way of thinking and learning that empowers complete foundational knowledge of the subject at hand.

When we’re not just equipping our students with a “math state of mind,” we’re eating, breathing and sleeping STEM. Our coaches are STEM professionals who just happen to be some of the nation’s best STEM educators as well as Georgia Tech and Emory University students that belong to groundbreaking research labs and aspire to become STEM leaders.

If you need coaching in a STEM subject or simply strive to achieve a deep, foundational understanding of the topic at hand, there’s no other academic coaching company to consider. Our coaching methodologies are unparalleled.

*Significant portions of this blog are adapted/taken from the titular New York Times article.